Meeting Reports

Reports of our meetings will appear here shortly after the meeting has taken place.

| Report by: Geoff Hodgson | ||

| Mark Chambers gave a wonderfully illustrated talk on the “History of the Teign Valley Railway”. He drew from his extensive collection of photographs of the line and took us on a journey from the old station at Heathfield Junction, through the tunnels near Longdown, to the end of the line at Exeter St Thomas. Built to serve the mines and quarries of the valley, the line was open to passenger services between 1882 and 1958. 85 people attended this talk. | ||

| Report by: Geoff Hodgson | ||

| Members of Christow WI gave a fascinating presentation on “Not Just Jam and Jerusalem: The Women’s Institute in the Teign Valley”. We learned that Christow WI was formed in 1932. It played a major role in the community, and a vital one during the Second World War. Its wartime service included producing and distributing food, knitting clothes, helping with child evacuees to Devon, and running a nursery to care for young children in the valley, when their mothers were working in the munitions factories in Newton Abbot or Plymouth. Respondents to our feedback questionnaire rated this event as our best overall, since we began surveying the membership in 2023. | ||

| Report by: Geoff Hodgson | ||

| Stephen Rippon, from the University of Exeter, gave a detailed report on the “Ipplepen Roman Excavations” of 2009-19. The site was discovered when metal detectors found a number of Roman coins in a concentrated area. Excavations found a village, with a continuity of settlement from pre-Roman times until the eighth century AD. Its findings have helped to enhance our understanding of our history in the South West. Respondents to our feedback questionnaire rated this talk as one of the two best since March 2024. | ||

| Report by: Geoff Hodgson | ||

| We held a joint social event with the Teign Valley History Centre. There was a quiz, mixing fun and history questions, a raffle, and celebratory drinks. | ||

| Report by: Geoff Hodgson | ||

| Philip Shute gave a talk on “Devon Churches”. Philip Shute has visited every church in Devon and Cornwall, blogged and researched the lot – that’s 931 churches. It took him 7 years. He talked about some of the wonderful churches in Devon and their history. | ||

| Report by: Geoff Hodgson | ||

| Todd Gray gave a superb talk on “The Blackshirts in Devon”. Oswald Mosley founded the British Union of Fascists in 1932. In the following year it established a base in Devon. It set up branches in several towns. The movement was significant in Devon until 1940, when its leading members were arrested and interned. Todd Gray gave a fascinating account of its history and its relevance for today. | ||

| Report by: Geoff Hodgson | ||

| Philip Badcott gave an enthralling talk on “The March of William of Orange through Devon in 1688”. He followed the 1688 journey of William Prince of Orange and his large army as he voyaged from the Netherlands to land at Brixham, and then rode through Newton Abbot, Chudleigh, Exeter, Honiton and Axminster on his way to London. William triggered the Glorious Revolution and was made king in 1698. Respondents to our feedback questionnaire rated this talk as one of the two best since March 2024. | ||

| Report by: Geoff Hodgson | ||

| The Annual General Meeting was followed by TV documentary on “Billy Butlin” and a discussion led by Tony Cook, who was involved in the production of the original programme. From the profits of his holiday camps, Butlin gave a great deal to charity. But there was a more seedy side to his life, which was related in this TV documentary. | ||

| Report by: Geoff Hodgson | ||

Woodbury Castle is an Iron Age hillfort near Woodbury, north of Exmouth. 17 members and friends of the Teign Valley History Group visited this Celtic hillfort on 11 June 2014.  It is a large construction, with high embankments and deep ditches for defence.  Pottery found on the site date it to 300 BC or earlier. Evidence now suggests that the Celts arrived in Britain in about 1000 BC. For our group it was a remarkable trip back in time, imagining what life must have been like here, between 2000 and 3000 years ago. Many of us will be descended from the Celts who lived in Britain at that time. | ||

| Report by: Geoff Hodgson | ||

| Members will remember the excellent talk in Christow by Terry Hearne on 9 April 2024 on “Saving Castle Drogo”. On 21 June 2024 Terry welcomed 11 members of our Group to Castle Drogo itself, near Drewsteignton. The magnificent building, now owned by the National Trust, is sited in a wonderful position, with spectacular views of Dartmoor. Its architect was Edwin Lutyens and it was completed in 1930. Terry led us around parts of the building and pointed to many interesting features. Its restoration has been a magnificent success. | ||

| Report by: Geoff Hodgson | ||

| Who would have believed that there were once about 80 water mills in the Teign Valley? Phil Collins gave a hugely impressive and highly detailed talk on water mills and other water-power use, from Chagford to Chudleigh. There were grain mills, saw mills, and many other uses of water-power. These included for farms, mining, tanning, tool manufacture and electricity generation. Phil showed many old photographs and paintings of mills in the area. Some of these buildings survive to this day. | ||

| Report by: Geoff Hodgson | ||

| After repeated days of rain, the old track bed was wet and muddy. This did not detract from the highly enjoyable trip by 22 TVHG members, back into our lost local railway past.

Guided by organisers and experts Charles Eden and Mark Chambers, we heard of the old single track railway that once served the Teign Valley. Stretching from Exeter to Newton Abbott, it was completed in 1903 but closed to passenger traffic in 1958. There are two tunnels on the stretch near Longdown. The Perridge Tunnel is blocked. But we walked from Longdown Station through the Culver tunnel to Dunsford Halt, no longer visible. But there is a sense of where the track was in the landscape.

A nostalgic and highly informative visit. | ||

| Report by: Geoff Hodgson | ||

| On 9 April 2024 Terry Hearne gave a fascinating talk on Saving Castle Drogo. He explained how Julius Drewe had made his fortune in retailing and had commissioned the building of a “castle”, set high above the River Teign. He commissioned the esteemed architect Edwin Lutyens, and construction started in 1911. Despite it being built of granite, the castle was no match for the Dartmoor weather. Major problems with leaks and water penetration emerged even before construction was complete. The castle was given to the National Trust in 1974. Terry spoke of the recent success of the National Trust in restoring the magnificent building and making it more weatherproof. | ||

| Report by: Geoff Hodgson | ||

| On 12 March 2024, Nick Walter gave a fascinating talk on “Mining in the Teign Valley”. 118 people attended, which is maybe an all-time record for the TVHG. Nick spoke about past mining activity in the Teign Valley. Mining is first recorded here in the early 1800s and it continued until 1969. The mines ranged from small workings for manganese, to the boom and bust of lead mining in the mid-nineteenth century, which saw many workers arriving from Cornwall. Later there were mines at Hennock and Bridford that gave settled employment to many, though not without the dangers of accident and illness. Nick presented several old photographs and was able to give biographical details of several of the pictured workers. This talk has received exceptionally positive feedback from those who attended. | ||

| Report by: Geoff Hodgson | ||

| On 13 February 2024, Richard Holladay gave a nostalgic and amusing talk to a large audience on “Exeter City Retailing Prior to the Second World War”. Using many retail advertisements from the 1880 to the 1940, with pictures of locations in Exeter, he showed how retailing changed over time and was very different from what it is today. He pointed out that much of Exeter City Centre was destroyed by Luftwaffe bombs in 1942. | ||

| Report by: Geoff Hodgson | ||

| On 9 January 2024, to a packed meeting, Josephine Collingwood gave a fascinating illustrated talk on “The geology of Dartmoor”. She explained how Dartmoor’s unique geology came into being, and explained the origins of its moorland, tors and valleys. Her account showed how the landscape had evolved up to human times, and why Dartmoor’s rich mineral deposits are on the edges of the granite massif. | ||

| Report by: Nick Kirkland | ||

| On 10 October 2024, Geoffrey Hodgson gave a well-attended talk on “Celtic Devon: Why Devon and Cornwall Have More in Common than we thought”. In terms of its culture and history, Devon is often considered to be very different from neighbouring Cornwall. Indeed, there are contrasts in landscape, place names, cuisine and culture. Many Devonians see themselves as Saxons. The Cornish describe themselves as Celts. Cornish was spoken in Cornwall until the eighteenth century. Cornwall harbours a sense of independence and separateness that is not found to the same degree in Devon. Geoff gave examples of Anglo-Saxon nationalism among nineteenth century historians. This has underpinned a Saxon bias in the interpretation of Devon place-names. The number of Celtic place-names in Devon has been greatly underestimated. For example, the name combe (meaning 'little valley') is also plentiful in France. This refutes the idea that combe is of Saxon origin. French etymologists uphold that combe is of Celtic derivation. The same must be true of combe in Devon, where it is a frequent place-name element. Likewise, the name tor (rocky peak) is likely to come from the Celtic word twr, meaning 'heap'. After proposing that Celtic place-names are much more common in Devon than previously acknowledged, Geoff used evidence from the Domesday survey of 1086 and a Devon legal report of 1238 to show that there were Celtic-speakers in Devon as late as the thirteenth century. Geoff has an online essay on this topic, which can be downloaded free of charge: Celtic Devon (geoffreymhodgson.uk). | ||

| Report by: Geoff Hodgson | ||

| The Teign Valley History Group held its Annual General Meeting on 11 July 2023. The Group is in good shape, in terms of its activities, finances and team spirit. It is planning to increase the number of its meetings. It works together with the Teign Valley History Centre to promote knowledge of local history. At the AGM, elections were held for the Group Committee and the following were all elected unopposed: Chair: Geoff Hodgson Vice-Chair: Tony Cook Secretary: Saul Ackroyd Treasurer: Julia Kirkland Four Other Committee Members: Maggie Bonnell, Nick Kirkland, Philippa May, David Taylor. At the well-attended AGM, some amendments to the Constitution were proposed by the Committee and accepted unanimously by the members present. The members awarded the preceding Chair, Graham Thompson, Honorary Life Membership of the Group. Graham was thanked for his outstanding work for the Group and his contribution to local history generally. After the AGM, Tim Lomas, from the British Association for Local History, presented Graham Thompson with an award for his huge contribution to the Teign Valley History Group and to the local community. Tim remarked that the Teign Valley History Group is one of the most active and well regarded. Following that presentation, Tim Lomas, who is also vice chair of the Devon History Society, gave a fascinating and instructive talk on “How can local history societies work effectively with communities?” | ||

| Report by: TVHG | ||

| For those of you who did not attend Dr Todd Gray's talk on Slavery in Devon what an event you missed! Todd has the authority and charisma to make everyone re-think the mainline thoughts on slavery. Too many people parrot statements without having the facts to back them up. The subject is far more complex. When Todd has expressed the lack of research behind these parroted statements, he has been subject of online abuse. It reminded me of John Stuart Mil who, wrote in 1856, about social tyranny. Have we learnt anything at all? No-one mentions the British and other Europeans enslaved by the Arabs of the Barbary states who were released by Admiral Pellew of Christow fame, or the trade of slaves between neighbouring African countries. He underlined how sparse research was- we simply do not know. At best we often have to rely on biased statements. Despite claims that Devon was a hotspot of slavery it does not compare with ports such as Liverpool, Bristol or London. Barnstaple only had a very small percentage of slave owners and many of them moved to seaports in the south of the county such as Teignmouth or Sidmouth which were pleasant places and where they could mix with Society. Some claim that the large houses in Devon were built using money earned from the slave trade but it appears that only three have proven links. Clearly, serious questions need to be asked and answered and we must not avoid the issues in what is not a very diverse community in the Teign Valley. Todd's talk was a wake-up call to all of us to examine evidence before pontificating on something we know little about to the harm of others. | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

| On 14 March, Graham Thompson presented the second half of his review of attitudes to vulnerable people in the form of an autobiographical account of his experience in medicine during his working life as a doctor. At the age of 16, his first experience of working in the health service was as what was then called a 'Ward Orderly’ (which would now be a 'Health Care Assistant') on a geriatric ward at what had been the Orsett Union Workhouse in Essex. This workhouse setting provided an interesting link with Graham's first talk which had described the creation of these institutions in the 19th century. Graham described the poor quality of care in this hospital with geriatric patients being very much a low priority for the health service. For several hours at a time he would be left in sole charge of 32 patients. He continued his medical training at Bart's in London, a major centre for medical education, where of the 100 students in his cohort just 8 - including him - had attended state grammar schools. Following his initial training he spent time in obstetrics in Northampton and delivered his first baby, named Graham in his honour! As a paediatric registrar, in Wolverhampton, he worked in a special care baby unit, where many of the babies were premature arrivals and were underweight, often due to the mothers' poor nutrition, he said. He decided to become a GP so he and his young family moved to Donnington in Telford, where he joined an established practice. This was a working class community, including an army base and a travellers' site. He told several stories of his experiences there, making the point that the medical practice was more or less the only form of external support for families in difficulty in this area. He did note the importance of inter-generational support - especially from grandmothers. However, when large authorities such as Birmingham cleared slums and rehoused families in places like Donnington, this form of support was often lost as different generations were separated. From 1987 the significant improvements to housing which helped to improve the health of the community, however this good news was counterbalanced by the introduction of new levels of bureaucracy in the health service, following the promotion of 'targets' by Tony Blair's government. Graham retired in 2006, moved to Devon, bought a boat and in 2010 convened a meeting for those interested in local history. And indeed the rest, as they say, is history - the Teign Valley History Group! | ||

| Report by: Maggie Walker | ||

| Sea serpents at Goodrington? Napoleon fathering a baby in Torquay? Lillie Langtry haunting a Devon care home? The shrieking nun of Ilsham Grange? These are just a few of the legends of South Devon relayed to the TVHG by Dr Kevin Dixon on 10th January. Most legends, Dr Dixon states, grow from repeated tellings of unauthenticated stories or from Pareidolia, when objects or certain phenomena are given meaning where there is none. Legends can also be deliberately invented; for instance, smugglers may have created ghost stories to deter people from going out at night while illegal dealings were afoot. And, of course, legends can be profitable. Ghost tours, haunted houses and spooky castles create business. Torquay museum had a record number of visitors after a child mummy supposedly left fingerprints inside its glass box and a beautiful blonde ghost was 'seen' hovering around the artefacts. Many people flocked to the Clipper Inn after an old man in a cloth cap was seen sitting in the pub when it was closed. This sighting very quickly became the legend of 'Old Jack' who had, before he died, frequented the pub in the same seat in the same cap. Most places have their own legends; they will be around, Dr Dixon tells us, as long as there are stories and, of course, there will always be stories. | ||

| Report by: Ian Menter | ||

| Just a few days before Remembrance Day, the History Group heard from Mark Bailey, a volunteer from the Commonwealth War Graves Foundation. He spoke about the work of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Over 1.7 million people who died during or as a result of the conflict in the two World Wars, are commemorated. The graves and memorials are at 23000 sites across 153 countries and territories. 12 thousand are buried at the largest such cemetery, Tyne Cot in Belgium. Those commemorated include many civilians as well as service people. The Commission is backed by the governments of six Commonwealth nations: Australia, Canada, India, New Zealand, South Africa and the United Kingdom. It has its origins in the First World War and the driving force behind it was Sir Fabian Ware. He was aware of the deep concern among families of those who had been lost, to ensure appropriate care was taken to identify bodies and mark the places of burial. Three key principles were established: the person should be named (where known) on the headstone; the headstones and memorials should be permanent; the headstones would have a uniform design, regardless of the rank of the person. Families could add an inscription to the headstone. Mark illustrated this last point by contrasting two headstones from Bovey Tracey Cemetery, one saying simply 'RIP', another with a more extended epitaph. Mark told the moving story of Jack Sadler, who was recently found to have died at the age of 17 following injuries sustained on D-Day. He is buried in Bovey Tracey and a street on one of the new estates at Bovey has been named Sadler Green, in his memory, thanks to the work of the Commission. The work of the Commission continues, with a huge maintenance and horticultural programme. There are also frequent reburials and rededications. The Commission's archive has ten thousand items. The Commission has a searchable website here | ||

| Report by: Maggie Walker | ||

| The Group's outgoing Chairperson, Graham Thompson, gave the first of two talks asking "What Can We Learn from our attitudes to the vulnerable through the ages?" Graham suggested that among the vulnerable we may consider the elderly and frail, those with a disability, the poor and children. Looking at prehistoric times, he suggested that we know little about how people of neolithic times cared for the vulnerable, although this was the time when it seems that forms of spirituality and concern for the soul began to emerge in society. By the early medieval era, Christianity had become the dominant religious persuasion in Britain and in Devon, we saw the establishment of a number of religious foundations. As people returned from the Crusades, a number of people were affected by leprosy and in order to reduce the spread of the disease specialist houses, leprosaria were built in order for these people to live separately from the wider community. These included establishments in Honiton, Barnstaple and elsewhere in the county. One of the last leprosarium to be built was in Newton Abbot, in 1538. The later period from the 15th to the 19th centuries saw the focus shift to first the Old and then the New Poor Law, with the emergence of alms houses and then workhouses as attempts to address the problems associated with unemployment and poverty. The later workhouses, including one at St Thomas in Exeter had separate wings for women, men and children and were also augmented by the provision of schools, apprenticeship systems, infirmaries and 'lunatic asylums'. The Exeter Asylum, later known as Exwick Mental Hospital was only closed as recently as 1986. Of interest in the Valley was Huxbeare House, a privately established asylum for just seven patients. The follow-up talk, covering the Second Elizabethan Age, in which Graham will directly address the question 'Do We Learn from History?', will take place at the meeting in May 2023. | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

On my study wall hang two wood carvings made by my great grandfather, one of which is a copy of the old door at Dartmouth Parish Church. They are exquisite but don’t bear comparison to the work by the Pinwill sisters of Plymouth. Dr Helen Wilson spoke to the history group on 12th July about the remarkable work by the sisters. Their father was vicar of Ermington and whose hobby was wood carving, their grandfather and great grandfather were shipwrights, so when their mother suggested that her five daughters develop an interest beyond the usual tea and gossip. This not only broke the mould of polite society but three of them started developing their wood-carving skills. This was such a success that they formed a company, Rashleigh Pinwill and Co. Violet, the youngest, was the most successful and her work is visible in churches all over Devon and Cornwall. Her work is a monument to the independence of women craftswomen which was so hard won, and is admirably displayed in Helens’ book, "The Remarkable Pinwill Sisters". Orders may be placed at sales@pinwillsisters.org.uk | ||

| Report by: Ann Mann and Philippa May | ||

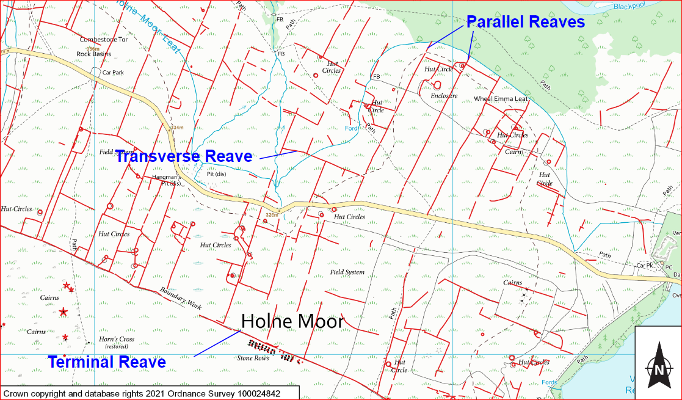

| Dr Bray, Senior Archaeologist of Dartmoor National Park Authority introduced himself to the well-attended audience, saying his specific interests were Geology and Archaeology. The subject of his talk covered the period 1600 to 1100 BC, the Middle Bronze Age. Much of his talk was accompanied by excellent slides of Reaves, Round Houses and Monuments. He aimed to explain how people lived at that time. There are over 11,000 scheduled monuments on Dartmoor with a lot still to be discovered. During the Neolithic period (New Stone Age) which started in 4000 BC, hunter gatherers settled down in one place and farming commenced. There are 3-400 hut circles on Dartmoor. These are stone circles within which is evidence of holes which were filled by posts to support the roof of huts, the best known & researched are at Merrivale, Buckland Common & Great Nodder. There are ‘neighbourhood’ circle groups, with different layouts suggesting several family dwellings, smaller workshops or animal enclosures. We know crops were grown because evidence of quern stones and rye have been discovered. The presence of domestic animals, livestock and vegetation is apparent and cow hair has been found used in decoration. More clues can be seen in the rich finds at the White Horse Hill dig, where sophisticated grave goods, jewellery, and advanced textiles & baskets were revealed. Around 1600BC land divisions started appearing. These are called Reaves. They are extended parallel stone borders, some of great length and of varying width. The earth disturbance in these patterns is still traceable. They occur in many different places and can be many kilometres long. We are still able to plot these because the ground on Dartmoor has never been extensively ploughed. It is not possible to say why they were placed as they were; most on the south side of the moor follow rivers. Could they have been social or political boundaries? Medieval boundaries often follow the path of reaves.  This shows the pattern of reaves on Holne Moor. Thanks to Dartmoor National Park Authority for permission to reproduce this. | ||

| Report by: Maggie Walker | ||

| A slightly different topic was introduced this month when one of the directors of the Bovey Tracy Paradiso Arts Centre talked about the history of, and hopes for, the project. The centre is based in the old King of Prussia pub, this title apparently not referring to a monarch but to a Cornish pirate/smuggler. We learned that before it was a pub, the building had been an Elizabethan farm, a hotel and a coaching inn. A piece of Tudor screen and Elizabethan fireplace have been incorporated into the architecture but the famous stuffed black cat of many a local story has not yet been located. Numerous grants, donations and the purchase of 500 shares in the project have now enabled the transformation from a pub into a fine modern gallery for Devon artists, four artists' studios and a community meeting room. Future plans include the development of a kitchen and high-end cafe/restaurant to be opened this summer and a one hundred seat cinema/performance space hopefully opening early next year. The project is named after the Cinema Paradiso in Wanaka, New Zealand. Further information can be found on the Paradiso website. | ||

| Report by: Maggie Walker | ||

| In its first ''live'' meeting for eighteen months, the History Group was treated to a fascinating talk by Professor Geoffrey Hodgson on the last invasion of the British Isles: the 1688 Glorious Revolution. Professor Hodgson stressed that much of the success of the invasion was due to the skills of William of Orange in both spin and detailed planning. Before leaving The Netherlands he made sure he had received appropriate welcoming ''invitations'' from certain people of power and then organised the distribution of pamphlets assuring the nation that he would ''protect English liberties and the protestant religion''. Even then it was not plain sailing. The October weather forced him to abandon his first attempt, but, undeterred, he quickly tried again and, this time successfully crossed The Channel with 463 ships bearing vast numbers of infantry, soldiers, mercenaries, dignitaries crew and slaves. The cavalcade was twenty ships wide as it sailed through the Straits of Dover, finally anchoring in Torbay. The invading army marched through the narrow, muddy Devon lanes singing Lilli burlero, a stirring English tune written by Purcell, and eventually, after a number of skirmishes, setbacks and delays, arrived in London where William and his wife Mary, were crowned. The impact of this invasion was profound and long-lasting. The deposing of the Catholic King James ensured the country''s Protestant identity but plunged it into recurring wars with both France and Spain for almost a century. It strengthened the power of Parliament, introduced the Bank of England and other financial improvements but, perhaps most importantly, it brought to Britain its first gin from Genever. | ||

| Report by: Maggie Walker | ||

| On July 13th we enjoyed a fascinating talk by Philip White, one time adviser on old farm buildings for Natural England, which may have persuaded some of us never to look at dilapidated barns and stables in the same way again. Threshing barns (the cathedrals of agriculture), granaries, shippens, shelter sheds, wagon sheds, stables, piggeries, ash houses, cider barns all provide key information in determining local landscape character and the history of local agriculture. Their architecture and the materials used to construct and/or renovate them tell us vital stories of how people have worked their farms over time. A closer look at the entrance to a threshing barn, for instance, might reward you with a discovery of graffiti in the shape of a daisy wheel which may be centuries old and was probably carved by one man in an idle moment to ward off evil or encourage a good harvest. These old farm building also often provide support for wildlife such as mice, bats, bees, owls and other birds as well as myriad plant life. Unfortunately their future is threatened by lack of maintenance, by changes in farming practice and building methods, by insensitive conversion and dereliction. If they do all disappear we may lose forever much historical information about the character and working practices of those who farmed the land for hundreds of years before our time. | ||

| Report by: Maggie Walker | ||

| At our Zoom meeting on 11th May, Dr. Sue Andrew, Chair of the Devonshire Association, highlighted some of the treasures on Sin and Salvation still evident in Devon churches. Until the Reformation, she told us, the church's role had been, through words, music and images, to guide a mostly illiterate population through their lives and save them from damnation after death. Images representing sin and damnation can still be seen locally, particularly in roof bosses, often overlooked when the churches were stripped in the mid sixteenth century. Ugborough church has roof bosses demonstrating the sins of lust and gossip. This latter sin is also represented in roof bosses at Bridford, Newton Abbot and Christow. Loose tongues were dangerous and insidious at a time when most people could not read. The boss at Christow is of two men gossiping, which is unusual as it was generally regarded as a female sin. An imp lies above the two male heads registering and recording everything they say ready to repeat their words on the day of judgement. Priests were given a handbook to help them guide their congregation through confession and reminders of the suffering of Christ. This suffering and the path to redemption can be seen in a beautiful stained glass windows at Doddiscombleigh church and in a faint and very rare wall painting in Ashton which also has an exquisite screen which would have been paid for by members of the congregation to demonstrate their piety and help them out of purgatory. Dr Andrew's last message to the society was to remind us of the amazing remnants of medieval ideas still with us in Teign valley churches which she hopes will continue to be cherished and guarded. | ||

| Report by: Maggie Walker | ||

| A Zoom meeting on 6th April took us, in the words of our speaker, Francis Fulford, on a ''big dipper'' of a ride through the history of Great Fulford House. We began with William de Fulford in ''time immemorial'' or 1189 at the coronation of Richard 1st then followed the fortunes of the Fulford house and family through 800 years of ups and downs. From fairly modest beginnings the family gained wealth and social standing through a series of advantageous marriages; by the year 1400, Baldwin de Fulford, was able to travel the world and accomplish deeds of great valour. The Wars of the Roses saw the family, together with most of the West Country, taking the Lancastrian side and ending with a Fulford hanged, drawn and quartered and family lands confiscated. The pendulum eventually swung back, the lands were restored and by the 1530s Sir John Fulford was able to extend the house to show off his wealth and status. In the civil war the family took the Royalist side; the house and lands were captured and looted by the parliamentarians but returned after the Restoration. The next few hundred years saw great improvements in the house and lands interspersed with periods of debt and time spent abroad to recoup. The Napoleonic wars brought a boom in land prices and profit for farming but the 19th Century brought financial disaster and retrenchment. In 1969 the farm saw its first new building since 1860. We were treated to some pictures of the gracious interior of the house and hope to be invited for a visit very soon. | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

| On Tuesday 12th January, Derek Gore took us on a fascinating journey in the footsteps of the Vikings in the West Country. We learned that the first Viking raiders were almost certainly Norwegian though the term ''Danes'' later came to describe both Norwegian and Danish invaders. The Norsemen would have had a fairly easy journey from their homeland to the Isles of Orkney and Shetland and from there would have travelled round the East and West coast of the mainland to eventually reach our shores. As their ships improved, becoming faster and more lightweight, they could be sailed or rowed to land on beaches or mudflats without the need of harbours. People in nearby villages who saw the Viking ships land would have been shocked and horrified with good reason. The attacks were savage. Churches, monasteries and rich or royal estates were mercilessly plundered and people slaughtered. Three kingdoms of what was to become England had been taken by the Vikings when King Alfred defeated them in Wessex but by the second Viking age, c980 – c1069, Ethelred of England was toppled by the Danish Knut who became king. In 1001 a Viking force penetrated the Teign and burned Teignton. The population sued for peace, in other words, paid the Vikings to go away, which they did, sailing off to attack Exeter. Stirring tales indeed. | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

| A first for the History Group! We held our first Zoom meeting on 10th November in which Richard Sandover gave a talk on the Domesday landscape of the Teign Valley. He does pioneering research on landscape development and we were lucky to persuade him to look at the Valley. The meeting was well received and the Zoom process worked well. You can watch the presentation here. You will need to enter the Passcode: hmB38*vW | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

| History Group member Sue Knox talked us through the origins of the reservoirs. A larger water supply was needed by Torquay when it expanded rapidly in the latter half of the 19th century. Several farms were flooded, whilst some were bought by the water board and evacuated because there was a risk of contamination to the water supply. These can be found on old maps which are easily available. Perhaps the most important to suffer was Clampitt farm, some old buildings of which still survive, but the farmhouse was demolished. This was the home of Elias Tuckett, a local Quaker, in the 17th century who was persecuted for his faith. He is buried along with several others in the Quaker burial ground next to the farmhouse but now overgrown with a tree plantation. There is a commemoration plaque near the site. | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

| The AGM minutes are available here | ||

| Report by: Maggie Walker | ||

| Archivist Helen Turnbull led us through the sometimes tumultuous history of the Clifford family at Ugbrooke House. Until the reformation the house had been leased to the precentor, head of music at Exeter Catherdral. In 1604 it was inherited by Rev Thomas Clifford who, like many of his descendants, improved his prospects by marrying a very rich woman. Thomas's grandson, another Thomas, inherited the house in 1660. He was a skilled financier and became a key figure at the court of Charles 2nd, receiving a knighthood and many valuable gifts including substantial lands which brought in huge revenues. After the Test Act (1673 – 1702) Sir Thomas, like all Cliffords a Roman Catholic, refused to take Anglican communion and had to resign. Catholics at this point could not hold any public office, pursue a professional career or go to university. This led to a significant drop in income for the Cliffords until the 2nd Lord Clifford married Anne Preston, an heiress from a Catholic family of considerable wealth who owned vast lands across England. When the 2nd Lord died he owned 5,000 acres. The fortunes of the Cliffords and Ugbrooke House varied wildly over the centuries. During the twentieth century it became a school for evacuees, a Polish convalescent home and a place to store corn. In 1957 it was sold to Hugh Clifford, later the 13th lord, for £5. The 14th Lord Clifford and his wife, an interior designer, slowly began to restore the house to some of its former grandeur and it is now occupied by their son. | ||

| Report by: Jerry Horsman | ||

| The Royal Clarence hotel went up in flames on 28 August 2016. Clearly the first firemen on the scene had only a limited knowledge of the construction of this 18th century building with much earlier origins and how it connected with nearby houses. Fortunately, Todd Gray was on the scene at a very early stage and able to give detailed advice on the whole complex. He had only recently been involved in a major research and recording operation. The fire service clearly recognised Todd’s expertise and hoisted him up on a giant cherry picker (plus blonde reporter) to assess the situation from above. This showed the solid stone foundation of a much earlier 13th century building and the plan of a medieval hall. The aerial view and the photos were an essential tool in preventing the spread of the fire to other buildings. What became the Royal Clarence Hotel was opened in 1769 by Pierre Berton and advertised as a coffee house, an Inn and also a hotel. It was the first use in England of this imported French word. In the 18th century it was the place to be for Exeter society with its assembly rooms, grand balls and concerts. In 1827 the Duchess of Clarence came to stay and the hotel acquired its new name. Over the years Todd has contributed massively to the study of Devon’s history. As always, he passed on his knowledge with great enthusiasm and good humour. A walk down Exeter’s High street and its back alleys is never the same again after listening to him. | ||

| Report by: Maggie Walker | ||

| On 10th September Dr Peter Selley gave a fascinating, if rather macabre, talk titled Grave Robbing in Devon. Prior to the Anatomy Act of 1832, only the cadavers of murderers had been available to the medical profession for dissection. Given that the London medical schools alone needed at least 500 bodies a year, this lack of corpses on which surgeons could develop their learning about human anatomy led to to a fairly brisk trade in grave robbing, mostly in major cities but also in Devon. Grave robbing was not just a trade in whole bodies; body parts were also sold, particularly teeth – thousands of teeth. Dr Seller told us several stories of Devon grave robbing: * In 1830, in Stoke Damerel (Plymouth),a gang of four grave robbers who disinterred up to 13 bodies were eventually caught and sentenced. * In Crediton a 12 month old baby was dug up. * In Barnstaple, James Bishop, a patient who died in the infirmary was dissected at the hospital while his coffin was filled with stones and buried. * In Exeter, a surgeon called William Cooke who, in 1826, had moved from Wolverhampton, advertised a course of lessons on human anatomy. The day before his first session, when the corpse he had ordered from London failed to materialise, he paid a grave digger named Giles Yard to disinter the body of Elizabeth Taylor, a 67-year-old widow, buried that day in St David's graveyard, and bring it to his house. Both Cooke and Yard were caught and charged. Cooke was fined £100 in spite of an outcry from the medical establishment. Yard was jailed in Exeter for 9 months then quietly released. It is possible that Cooke had been 'shopped' by fellow Exeter surgeons who were jealous of him moving into 'their' territory. His reputation never recovered and he died young. Yard went from bad to worse and was finally transported to Tasmania for stealing a scythe. Members of his family flourished, however, and some of their descendents now live and flourish in the USA. | ||

| Report by: Maggie Walker | ||

| On 16th July Dr David Stone gave an absorbing account of Eastern Dartmoor in the age of the black death. From mid 13th Century to the eve of the black death the area had been enjoying a benign climate and life for many had been improving though there were still a considerable number of unfree peasants reluctantly labouring for their lords and a growing landless population dependent on labour for survival. In late autumn 1348, the plague arrived in Devon and by spring of 1349 was at its height. Symptoms included putrifying boils, fever and stupor. Some would recover, many died within five days. Two thirds of the population of Dartmoor may have been lost. The area was worse hit than the rest of England. The immediate effects were grim: stinking churchyards, devastated families, abandoned farms, unharvested crops and animals dying from neglect, but in many ways the black death changed the course of the middle ages forever. Within forty years the population had largely recovered (more rapidly than the rest of England). There was more land per head of population and it was reoccupied on better terms, wages improved and serfdom declined as Lords had to negotiate with tenants. Tin production and demand increased. The social and economic changes continued. With rising wealth came greater consumption, better food, drink and clothing, churches were gradually embellished and decorated. This incredible recovery and survival from a devastating pandemic is to the credit of the people who lived on Dartmoor more than half a millennium ago. | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

| The AGM minutes are available here | ||

| Report by: Maggie Walker | ||

| On 14th May, David Taylor took us on a fascinating journey into the Medieval Teign Valley 1066 - 1525. Unless you were one of the very small minority of Norman nobility who had been gifted land by the King, it was probably, as David made clear, a fairly miserable time to be alive. Villeins, Bordars and Cottars were all in thrall to the ruling class. Serfs – about 10% of the population - were virtually slaves. Sheep were the main source of income, not for meat but for wool. From 10th to 14th century the woollen industry brought significant wealth to the landowners. 90% of the population was involved in agriculture. The Agrarian Crisis (1314-22) accounted for the death of 10-15% of the population of England. Food supplies failed, people starved, cattle and horses became diseased, and crime increased. 20 or so years later the Black Death arrived - in late summer 1348. This killed 45% of the population. It was a time of terrible inequality where the rich (who were very rich) grew richer at the expense of the poor. Actually it all sounds rather familiar. | ||

| Report by: Maggie Walker | ||

| On 12th March Don Archer led us on a fascinating journey through the industrial archaeology of the Teign Valley defined as 'the bits of industry which have been left behind.' We began our journey at Castle Drogo where the architect Lutyens generated electricity for the castle using a turbine on the Teign. This generator has been restored by the National Trust and now provides about half the electricity for the castle. Further down the valley, Chagford was the second town in England to have public electric lighting, generated from a turbine built on a leat diverted from the river. From Chagford we meandered down to Fingle Bridge with its corn-mill water-wheel and on to Steps Bridge where a leat still diverts from the river under the road bridge to the iron mill where the Morris family produced fine edge tools using a water wheel until 1937. The mill is still in use, now powered by electricity although the wheel is still there. A wonderful selection of the old Morris tools can still be seen in the museum at Bicton Park. A leat from the Teign still runs beneath the old Baptist chapel at Dunsford but the old mill at Dunsford is now a block of flats. We also heard about the many mines in the valley where speculators have delved for copper, lead, zinc, silver, iron, magnetite and barytes with varying success. Evidence of many of these mines still remains; I'm sure we all recognise the lead waste piled beside the Valley Road. | ||

| Report by: Maggie Walker | ||

| Katherine Findlay from the Devon Heritage Centre presented us with the fascinating tale of a Teignmouth man who changed the fortunes of Iceland in the late nineteenth century. The talk was based her book called "The Icelandic Adventures of Pike Ward" in which Katherine has edited his diaries. Pike Ward was the eldest son of a successful Teignmouth ship-broking family. When his father died, rather than following the family business, he headed to Iceland. Iceland had long been a place of myth and legend but at that time it was a desperately poor country governed by Denmark. Infant mortality was high, starvation was common and the tiny community lived from hand to mouth. The population was only allowed to fish close to shore and any excess fish had to be bartered with the Danish fishing companies for vital goods. Pike Ward revolutionised the Icelandic economy by buying, for cash, the smaller fish unwanted by the large Danish companies then showing the local community how to dry, salt and preserve them. The businesses he set up thrived. Dried and salted fish was very popular in England, particularly Devon, where it was made into fish pies and a dish called Toe Rag. The cash, sometimes gold, paid by Pike Ward for the Icelandic fish, enabled the community to thrive for the first time in centuries. Pike Ward stayed in Iceland for 22 years, only returning to Teignmouth for the harsh winters. He learned to speak Icelandic and made long-standing friendships with local people. Many Icelandic people still regard him as a key figure in the movement which finally led to Icelandic independence from Denmark. When Pike finally returned to Teignmouth he decorated his villa with Icelandic carvings and called it, of course, Valhalla. | ||

| Report by: Maggie Walker | ||

| Derek Core from the University of Exeter gave a fascinating talk on the Roman conquest of the South West Peninsular. Previous studies had suggested that the Romans never crossed the Exe but there is now considerable evidence that they reached as far as the Isles of Scilly. The invading force would probably have been an army of 10,000. Half would have been legionnaires, already Roman citizens, the other half auxiliary soldiers. The local population at that time (AD 43 onwards) would probably have been no more than 100,000, so the impact on food supplies, local resources, land and culture would have been profound. Initially the Romans would identify trouble or insurrection and summarily subdue it. Once the population had been brought under its control, the soldiers would then remain in their forts undertaking a policing role. There was little winter campaigning. Most soldiers lived in the forts from October to March unless they were needed to suppress trouble. The picture of the conquest is still unfolding: Roman forts are still being discovered in Devon and Cornwall at, for instance, Calstock and Restormel. Aerial photography has been used to identify the classic rectangular shape with rounded corners. Some forts were built from scratch by the Romans, in other places they were erected on the sites of old iron-age forts. Aerial photography has also revealed sites of many Roman villas or single family farmsteads. It was assumed that these single family homes, with or without surrounding ditches, were where most of the population of Devon and Cornwall lived, rather than in hamlets or villages. This view however is currently being questioned by the archaeological digs at Ipplepen which have uncovered a rural settlement from the Roman period with several homes connected by a road. It is clear that in this field every new discovery will uncover as many questions as it answers. | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

I would have liked to have heard the history of who had set the service initially and what freight it carried. There are references to Great Western Railway shares in probate records of local residents. There are also a number of references to the running of the railway in the 20th century found in the book, Teign Valley Tales, copies of which are available at Christow and Dunsford Post Offices and at the Artichoke Inn. People used the service to travel to school in Newton Abbot or to go to work in Exeter. The line was used in the Second World War to transport injured soldiers to hospitals when the main coastal route was either damaged by enemy action or unsafe due to weather conditions. The track can still be seen at various locations although houses have been built over the track at places, or turned into gardens and Perridge Tunnel has been filled in after a collapse. No one was hurt in the collapse but Exeter Maritime Museum stored boats it was unable to show at Exeter Dock in the tunnel and some of these are buried still. I wonder what archaeologists will make of that in 100 years’ time? At the meeting a question was raised on the use of the station yard as a cattle market. Mrs Brightmore-Armour (whose records have been donated to the Archive) records some observations by Cyril Smale who told her that the market was held every 3 months after which the cattle were transported to Exeter or Newton Abbot. The practice stopped in 1951. | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

| The talk was on Crime and Punishment in the 17th century. It was to be given by Dr Janet Few but instead she sent along Mistress Agnes, direct from the 17th century, who had greater knowledge of such things. We knew this because not only did she give such a convincing account but was dressed in a costume appropriate to the 17th century. She had also accumulated rather grizzly objects used back then such as a hangman’s noose, an iron mask to subdue a scold, or garrulous spiteful wife, and other gruesome objects of torture. Any husband could parade such a horrible woman around the village to humiliate her. Clearly women had to obey their husband or else! However, women generally were not presented to the courts and men comprised 85% of the criminal fraternity according to court statistics. Women’s ‘crimes’ were generally dealt with by the community who humiliated or even killed them after they were accused of adultery, prostitution. Illegitimate birth and witchcraft. | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

| The AGM minutes are available here | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

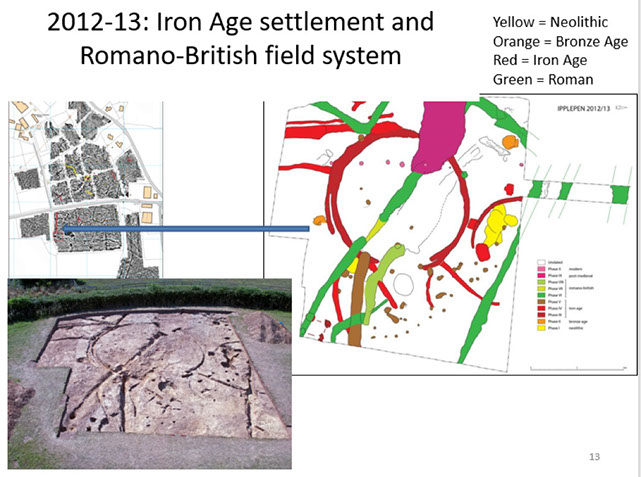

| For our May meeting Professor Stephen Rippon, Professor of Landscape Archaeology at Exeter University updated us on the excavations at Ipplepen. He first explained that the greatest Roman influence was in the Central Province, which stretched down the middle of England to the Blackdown Hills. Beyond that the Southwest appears to have been less affected by the Romans. There is a distinctive character of landscape and society in the Southwest. Prior to the arrival of the Romans the Dumnonii tribe was well established in Devon but it left no coins, so we understand little about them. Neither did they adopt the Roman habit of building Villas. In fact, there are only 2 in the Peninsular. They did, however, have South Devon Pottery which is found almost entirely confined to the County. Pollen analysis shows that agriculture changed very little between the Iron Age and the early medieval period. (400 BC – 800 AD). Approximately half the cereal crop was Wheat whilst the remainder was split equally between Barley and Oats.  The Ipplepen sites sit South of the modern village. The dig began in 2012, the sites being chosen mainly after geophysical surveys. Examination shows there was an Iron Age settlement with a Romano-British field system. The sites of roundhouses were marked by circular ditches inside which were the houses. The ditch was for drainage of water pouring off the roofs. (See image) A different site showed a very well made Roman road, part of the route between Exeter , Newton Abbot and Totnes. Nearby is a Christian cemetery with the bodies being placed roughly East/West. It is remarkable that the bones survived as the soil is generally acid which would normally dissolve bones. This site may have been lined with lime blocks so raising the pH. There was, also, evidence of iron working with chunks of iron being dug up, indicating that a blacksmith operated nearby. The site was abandoned in the 8th century when the ‘modern’ village of Ipplepen was created to the north. More information can be seen on the Exeter University website | ||

| Report by: Martin Watts | ||

| Watermills were formerly a common feature of the Devon landscape. Many share their origins with other historic buildings such as churches and manor houses, but because they are working buildings that were frequently rebuilt or modernised, they are often glossed over in local historical, landscape and building studies. My talk illustrated the background and development of water power in Devon over a period of some two millennia, with particular reference to the Teign valley. | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

| Fingle Woods have been an important part of the local economy for generations. Cranbrook and Prestonbury Castles are well known but recent clearing of the area along the gorge has revealed a number of prehistoric stone circles which surely were linked to each other in a Stone Age community. At the time of Domesday the woods were divided between a number of owners who lent their names to the various stretches along the Teign Gorge; names such as Whiddon Wood, Charles Wood, Hall's Cleave, etc. St. Thomas Cleave was probably named after the murder of the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1170 as a lot of land here was owned by William de Tracey, one of the implicated knights. A lot of information comes from the Exeter Domesday which is in Latin requiring lengthy translation and an understanding of abbreviations. An understanding is needed of what a 'wood' was. It was probably a collection of trees with areas of cultivated grass between rather that a continuous stretch of woodland. Confusion also arises with the non-standardisation of measures of length so a rod may be anything between 18 and 24 feet in length (5.5 - 7.32 metres) but these problems can be overcome to assess the size of Fingle Woods. Cultivation of such a steep sided gorge was never going to be easy and tree planting was the only option. Martyrdom All schoolchildren will have heard of the murder of Thomas a Becket at Canterbury Cathedral. The knights involved misunderstood their king's wishes and when they discovered their error tried to make amends so in 1173, some years after the event, (did he take some persuading?!) William de Tracey gave 1500 acres (St Thomas Cleave) to Canterbury Cathedral to help the monks' income and assuage his guilt. Customs of the Manor Each manor established customs or rules on how much access the peasantry was allowed and what they could do in the manorial estate. The parish of Doccombe has particularly good records. It lists who could collect items from the wood, graze animals there or carry on an industry there - for a charge. This created tension between the landlord and the peasant. So, a wood warden would be appointed each year. The only way to get out of this was to appoint (& pay someone else to do it.) Today we look on woods as being tranquil places in which to walk and to admire the scenery whilst walking the dog. In earlier days they were a hive of industry. eg: * Tanners used bark in the process of making leather. If too much was stripped off the tree, the wood would die depriving the other villagers and the landlord of their living. This had to be controlled. * Large trees were not common because the soil was thin, and rain would wash away what there was exposing the roots. Therefore, coppicing was practised. Young trees had their stems cut down to act as poles. * Colliers, of which there were 7 at one time in Moreton and not to be confused with coal miners, leased places to set up their Charcoal pits. Charcoal was used in fires, smelting tin and heating wool combs among other things. * Tourism, started taking hold in the 19th century when railways arrived as it was now easier for the ordinary individual to travel distances. Previously only the richer parts of the population who saw countryside estates as a place for hunting and shooting, had been involved. * At Fingle Bridge a café was opened. However, the plans for a railway to Chagford as a branch of the Teign Valley Railway never came to fruition. By this time Fingle Woods had had a variety of owners and often were somewhat neglected but the Elmhirsts took over in the 1930s with definite ideas on how to develop the area. Dorothy Elmhirst was a very wealthy American whilst Leonard had an interest in forestry, a subject just beginning to take off. They started with the Dartington Estate which was run down at the time and went on to create a large number of independent business concerns. One of their wishes was to buy lots of woodland areas and sawmills whilst researching how to best grow trees. Their wealth allowed them to do this without constraints of time to make a profit. One of these areas was Fingle. It is difficult now to understand how badly-off Devon was economically at the time. They had what today we would call green credentials but they were also passionate in providing employment for local residents. In addition, they were keen on education, and tourism. | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

| Elly Babbedge told us about her research into the way the residents of Cheriton Fitzpaine looked after their fellow villagers in the 18th and 19th century. They were years ahead of everyone else in the way they dealt with 'lunatics' sending one of them to a Doctor Southcombe in Rose Ash 15 miles away. He 'did not hold the insane person responsible any more than if he had a fever and held the opinion that madness could proceed from either the wounded spirit or a disordered body'. He, therefore, held 21st century views some 250 years before in contrast to his colleagues who incarcerated anyone with a mental illness living in towns and cities in places like Bedlam. The terminology has now changed of course. Elly went on to describe how the village supported Humphrey Winter throughout his 52 years of life. He was orphaned and had no family to care for him so the parish paid his board and lodging providing him with clothes but not apprenticing him as was the usual case. Why this happened is a mystery but he was presumably not felt capable of such work. It looks as if the absentee landlord, somewhat unusually, had great affection for the village as he paid for the erection of the Church House, the longest thatched building in Devon, which housed the poor, had a room for the Vestry and court and later the school which only closed 5 years ago. In addition he donated a field for 'physical recreation' although this is now a car park! There are many more examples of how the village cared for its parishioners falling on hard times which are described in Elly's book 'Cheriton Fitzpaine, A Sense of Community', available on Amazon. Their enlightened attitude contrasts with how towns managed. | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

| There was a bit of a scramble to find a speaker at our last meeting in September when the booked speaker told us he had double booked the evening! We were very grateful to Robert Hesketh who was able to step in with 48 hours' notice. Robert gave a very interesting talk on Tudor & Regency buildings in Exeter. Most of us scurry round the city looking at eye level into the shops and fail to notice what's above us. Once you learn to do this you discover so much more. Exeter is blessed with many buildings from yesteryear. It is impossible to list them all. He started with Moll's Coffee House (1596) and its neighbour, Tea on the Green, but the largest collection is on the High Street with their Tudor and Stuart facades above eye level. Some of the buildings are narrow as they had to fit the Burgage plots behind or had upper jetty floors which hung over the street. The second part of the talk involved Regency buildings. There was rapid expansion of Exeter between 1800 and 1840. This led to major overcrowding with 70,000 people crammed into 3000 houses. This was clearly a health hazard. The sewage which had previously flowed down the street was confined to covered culverts. Trade grew, roads were widened and the obsolete city gates were removed. Water was taken from the Exe upstream to avoid pollution. These improvements led to a lot of new building in the Regency style which attracted travellers unable to holiday abroad due to the Napoleonic Wars. The terraces and crescents are to be seen in Southernhay, Barnfield Crescent and Pennsylvania. The moral of the talk was that it is important to look up when appreciating the huge wealth of ancient buildings. | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

| Wes Key was our speaker on 11th July. He is a Master Mason but having gone away to gain a degree in Building Surveying he took on the job of looking after the National Trust buildings on Dartmoor, not least of which is Castle Drogo. He gave a very thorough account of how Castle Drogo was built and why this led to massive repair work to overcome the various leaking problems. The illustrations he used brought home what a massive job this has been. Julius Drewe had made a fortune in business and asked Sir Edwin Lutyens to fulfil his dreams of designing a castle as his home. To give an idea as to how extensive the work has been 600 windows have had to be removed, repaired and replaced. Completion of the work is expected next year. | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

| The AGM minutes are available here | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

| Bill Hardiman, the local historian from Moretonhampstead spoke to us in June on the history of his town in the 17th Century. It was a very detailed history and I cannot possibly do it justice in the space available. The only answer to this is for you to become a member – the advantage is that you then get to help choose the subjects discussed. Moreton’s parish registers go back to 1603, the year of Elizabeth 1’s death. At the time the law said that at burial bodies should be wrapped in ‘woolen’ to protect the wool trade. This helped Moreton considerably as they were in the forefront of the woollen industry. Other documents show that King John awarded the town a market in 1207 which made it a borough. A problem arose that Chagford was also awarded the right to hold a market a few years later which resulted with both towns hurling insults at each other ever since! No older buildings exist nowadays as a result of a number of fires but pictures survive of jetty houses in which the upper floor projected beyond the line of the ground floor. In any historical research it is important to go back to original sources to test the myths and legends that grow up with the passage of time. Bill with volunteers have been able to look at numerous documents. This is the advantage of local history over the rather general overview that occurs in national history. The geographical extent of Moreton depends on which areas looked at. For example, the Manor of Moreton is mentioned in the Domesday Book but this only constitutes about 60% of the Parish with about 20% attributed to Doccombe Manor. Sir William Tracey left the Manor of Doccombe to Christ Church, Canterbury for a monk to take over its affairs. Maybe he did this in recompense for being involved in the murder of Thomas a’ Becket. He never implicitly admitted this but the attribution of St Thomas to the churches in Dunsford and Bovey Tracey does suggest a connection. On the other hand, Bovey historians, Viv Styles and Frances Billinge, have not found any documentary evidence for the connection. Moreton Manor was owned by the Courtney family between 1300 to 1890 when it was sold to the Smith family founders of WH Smith, the stationers. Sir William Courtney married a rich heiress and when she died he married Sir Francis Drake’s widow so financially he was well set up. However, he was dissolute and tended to spend beyond his means. He upgraded Powderham Castle but was always in debt. He probably had conflicting thoughts about religion. He grew up in disturbed times with the constant two-ing and fro-ing of allegiance to either Protestant or Catholic churches. His Grandfather who brought him up was Catholic but it was dangerous territory. Several of his estates were forfeit to the crown but he managed to hang on vast estates in Ireland. Despite his large income he found it necessary to mortgage Moreton Manor to Sir Simon Leach in return for £3000. Leach was bale take all the income from the Manor and to hold the advowson, the right to appoint Rectors to the church. Simon Leach's father was a blacksmith who probably made the gates at Crediton Church. Simon was sent to train as a lawyer, a very lucrative profession and which set him up to purchase property. Later when John Southmead took over the advowson he appointed Francis Whidden a puritan to the living of the church. He tried to ban games, Maypoles, Ale houses (as there were 16 of these he may have had a point!) and castigated tradesmen for Sunday trading. The place of Moreton in the Civil War is controversial as although there are reports of people from the town being involved did this mean the whole town was for Parliament? It probably served as a centre for surrounding villagers to congregate in banned Conventicles or meetings. If discovered such people were fined. Manor life was controlled quite fiercely by the Lord of the Manor (at least if he was resident and this continued until the Copyhold Act of 1926 when ownership law was altered. Before then regular courts were held to settle disputes and tithes were collected to pay both the Lord and the rector. There are a lot of documents regarding Timber sales. Wood was valuable source of building materials and other trades and was strongly regulated so Tanners and charcoal burners leased the right to bark and some wood. Here I will have to leave it but it would prove interesting to explore further life in the Teign Valley to emulate the research in Moreton. I hope to set up a group to this end so please contact me if interested. I wonder if this is something local schools would be interested in? | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

| When a medieval craftsman devoted hours of his time to carving out the end of a church’s bench or pew he did so as part of his service to God. This service is largely forgotten as their names are rarely recorded. What is quite remarkable is the fact that there don’t appear to be any repeated carvings. Such craftsmen must have kept to a very localised area. I am sure the carvings are virtually ignored by us when we visit one of the many parish churches within Devon. As a result of a detailed exposition of these carvings by Dr Todd Gray, Research Fellow from Exeter University, members of the Teign Valley History Group are now a lot more conscious of them. Dr Gray, who talked to us in April, has visited every parish church in Devon (where there is the largest collection of Renaissance carvings in the country) & most others in the Greater South West of England. He has also seen a lot in East Anglia . Unfortunately it is not possible to do full justice to Dr Gay’s talk because we cannot reproduce his vast array of photos here. His book, Devon’s Ancient Bench Ends published by Stevens Books in Exeter, gives much more detail. There is a significant difference between those carvings in East Anglia & those in Devon, probably because of influence from those countries trading directly with East Anglia i.e. Germany & Holland & with Devon from France & Italy. The earliest example he has found comes from the 15th Century but there are earlier records e.g. in the Exeter Synod records they are mentioned in 1287. This is all very interesting but why does it matter? | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

| Last month I wrote about the excavations at Tottiford reservoir. Now I am covering that part of Jane Marchand’s talk on her remarkable finds on Whitehorse Hill. It is difficult to convey every part of her talk in such a short space so this is very much a précis. One wet & windy day in winter Jane had a phone call from a Dartmoor Range Warden telling her that he had found a cist (stone lined burial chamber) on Whitehorse Hill. It is quite isolated being away from any roads, very boggy & in the firing range. It is 600 metres above sea level & the views are panoramic. It is also surrounded by the sources of 5 rivers which may be significant. Because the cist was in danger of falling apart & to protect it from interference from local walkers a wall was built in front of it & it was scheduled by English Heritage. It appears to date from the early Bronze Age & possibly the Neolithic Age. When the lid was lifted red fur & fragments of bone were seen. As this was lifted out a bead fell from it so it was realised that this was a significant find. The light was failing & the weather was atrocious: the fur had to be wheeled down to the road on the northern edge of Hangingstone Hill in a wheel barrow & the next day was taken to a Wiltshire laboratory to a conservator. It had to be treated quickly as it would have deteriorated in the air. In Chippenham it was found that there were four layers to examine. Firstly cremated remains with charred pieces of bone were removed. The red fir had been used to wrap up grave goods. There was a flattened bag which contained a large number of beads underneath which was a leather & textile object beneath which there was a base made of Purple Moor Grass, still to be found on the moor. About half a skeleton was recovered but it had been heated to such a high temperature in the cremation that it destroyed the DNA. The skeletal remains suggested a slight person, aged about 18-25. Both Oak & Hazel were identified which were carbon dated to 4000 years ago. The second layer contained the basket which was sent to the British Museum where expert stitching was demonstrated with cow or possibly Aurok hair. It was exquisitely made using a coiled technique from Lime bast i.e. the inner fibrous part of the bark. It was there to hold all the belongings. The leather object is probably calf skin & has a fringe of tassels & is joined to woven nettle. It is probably a portion of a cape & denotes a high status burial. A necklace of clay, amber & tin, a beautiful & intricate wrist band & large wooden ear studs were assembled. The team then moved onto the environmental information: a 160cm sample of peat was extracted & revealed 5 layers of volcanic ash covering the period 2000 BC to 900 AD. This was the dust from volcanic eruptions in Iceland. These were all known eruptions but for some reason did not include those from Hekla, the most active Icelandic volcano. Research is still ongoing in pollen analysis & fungal spores which will give evidence of animal involvement. In summary here was a cremation of a highly regarded member of the community, probably a young female, which contained a lot of organic material which has excited the interest of many archaeologists around the world. Jane Marchand expects more information to come to light in the next year. | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

| The History Group recently heard Mark Cottle of Explore History in Chudleigh talk about the history of Exeter Cathedral. There was a period of cathedral building between the 11th to 16th centuries which has never been equalled. Architecture changed as the years went by but there are 4 main styles recognised: Norman, Early English, Decorated Gothic of which Exeter is the best example in the United Kingdom, & Perpendicular Gothic. The Fabric Rolls survive in an almost continuous run telling us what work was carried out & who did it. The stone mason, Thomas of Whitney, had to calculate the various angles of the masonry to make sure the stone fitted accurately & the fact that it stands after almost 1000 years suggests he got it right. So why did the cathedral exist? In the Norman period it demonstrated Religious, Political & Military might. The Bishop demonstrated his power by erecting the largest throne in the country. By the time of the Gothic period the religious theme had come to the fore. Building took place between 1133 to the end of the 14th century. On entering the cathedral you are struck by its 300 foot length only interrupted by the organ which is in the best acoustic position. Look up & admire the Gothic vaulting with exquisite palm like fronds held together by the roof bosses. Enthuse over the floods of light. Take a closer look at the roof bosses which are incredibly well carved, colourful & detailed. The carpenters demonstrated their skills by carving the miserichords with meticulous detail in about 1316. The Exeter Book is an Anglo Saxon Codex dating from 970 AD & is one of only 4 surviving copies & is likely to be on display when the refurbished Cathedral Library is re-opens soon. It is important because it gives an insight into thinking before the Normans took over. | ||

| Report by: Graham Thompson | ||

Did you know that the best seaman of the 19th Century was connected to Christow? Those of us who attended the excellent talk given by Graham Thompson at the Teign Valley History Society heard an interesting story of a Cornish boy who led a life worthy of a blockbuster movie. Edward Pellow later Vice Admiral of Great Britain and 1st Viscount Exmouth rose to virtually the top of the Navy due almost entirely to his expertise rather than by patronage; an unusual attainment in the 18th and early 19th Centuries. Even as a lad Edward was mad about the sea. At 13 he joined HMS Juno in 1770. HMS Juno was sent to the Falkland Islands to see off the Spanish who claimed sovereignty by virtue of an ancient grant by the pope and who had evicted the British garrison. Sound familiar? He was given his first command of HMS Hazard.at the age of 23. After 8 months he took command of the HMS Pelican. With this boat he raided the coast of France. The admiralty was so pleased they promoted him to Post Captain in May 1782. .He continued rising through the navy fighting the French. When a ship called the Dutton was sinking in Plymouth Harbour he immediately took charge using his sword to maintain order among the drunken crew. He saved the lives of many women and children. For this action he received the Freedom of the Borough of Plymouth and created a Baronet. During a rare period of peace he became MP for Barnstaple. War was again declared in 1803 and in 1804 he was promoted to Rear Admiral of the White & to the East Indies command. In India Pellow’s job was to subdue the pirates, privateers and the French fleet as well as protecting the East Indiamen. Whilst Edward was away he left his wife to buy an estate and she bought Canonteign Estate in 1811. He appears to have tried living at Canonteign Manor but grew bored with watching the wheat grow! Lady Pellew also bought West View House in Teignmouth, now Bitton House which Edward came to look on as home. He preferred sea views! In 1814 he was promoted to Admiral of the Blue and became Baron Exmouth of Canonteign. In 1815 he was sent to deal with to liberate the Christian slaves and to punish the Dey of Algiers. His action was very successful. | ||